How I Navigated Inheriting Assets Without Losing Value — A Real Cost Breakdown

Inheriting wealth sounds like a win, but I almost lost thousands to hidden fees and poor planning. From legal bills to tax traps, the costs add up fast. I learned the hard way — emotional decisions, rushed moves, and not asking the right questions. Now, I’m sharing what actually matters when handling inherited assets, how to spot unnecessary expenses, and where smart moves can save you serious money. This isn’t theory — it’s what I tested, lived, and wish I knew earlier. The difference between preserving value and eroding it often comes down to awareness, timing, and discipline. This is the financial roadmap I wish I had the day I stood in the lawyer’s office, holding documents that felt more like burdens than blessings.

The Moment Everything Changed: Receiving Inherited Assets

The first call after a loved one’s passing often isn’t about grief — it’s about paperwork. Who is the executor? Where are the wills? What accounts exist? In the fog of loss, financial decisions must be made quickly, yet they carry long-term consequences. Inheriting assets is not simply receiving a windfall; it is stepping into a complex system of legal, tax, and logistical responsibilities. Many families, including mine, initially see the inheritance as relief — a cushion, a home, a nest egg. But without clear guidance, that relief can quickly turn into regret.

When my mother passed, I inherited her home, a brokerage account, and a retirement fund. At first, I viewed these as gifts — tangible proof that she had prepared. But within weeks, I faced decisions that no one had warned me about. Should I sell the house immediately? Could I access the retirement funds without penalty? What if there were debts tied to the estate? The pressure to act was immense, fueled by family expectations and my own desire to ‘set things right.’ I almost liquidated the brokerage account within the first month, believing that cash in hand was better than uncertainty. That impulse, I later learned, would have triggered unnecessary taxes and fees.

A close friend of mine made that exact mistake. After inheriting her father’s investment portfolio, she sold everything to pay off personal debt and consolidate funds. She didn’t realize that selling all positions at once locked in capital gains, nor that some assets had low cost bases, meaning a large portion of the proceeds would go to taxes. By acting too fast, she lost nearly 25% of the portfolio’s value in combined taxes and fees. Her story is not unique. Studies show that nearly 40% of heirs make significant financial changes within the first six months of inheritance, often without consulting a financial professional. The result? A substantial erosion of value before any long-term strategy is even considered.

The lesson is clear: pause. Inheritance is not an emergency, even when emotions say otherwise. The first step should never be a transaction — it should be assessment. Take inventory of all assets, understand their structure, and identify the legal and tax implications of each. This includes reviewing titles, beneficiary designations, and any outstanding liabilities. Only after this foundation is laid should decisions about selling, transferring, or holding be made. Acting with intention, not impulse, is the first line of defense against preventable financial loss.

Mapping the Hidden Costs: What No One Tells You

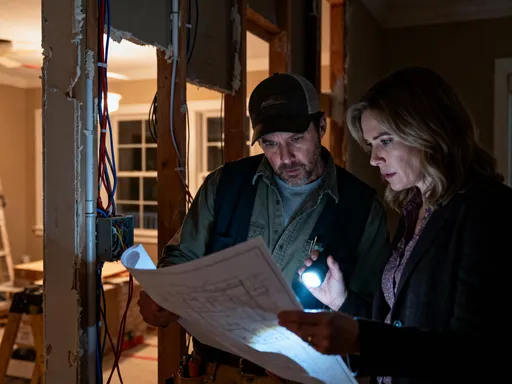

Most people assume that inheriting assets means gaining wealth outright. In reality, every transfer comes with a price — some visible, many hidden. These costs are rarely discussed in will readings or family meetings, yet they can quietly drain tens of thousands from an estate. Probate fees alone can consume 3% to 7% of an estate’s value, depending on the state and complexity. These are court-supervised processes required to validate a will and distribute assets, and they are not optional for most physical property or non-designated accounts. Legal consultations, while necessary, add another layer: hourly rates for estate attorneys often range from $250 to $400, and simple cases can require 10 to 20 hours of work.

Then come appraisal fees. If real estate is involved, a professional appraisal is typically required to establish fair market value for tax purposes. These cost between $300 and $600 for a standard home, more for larger properties. Similarly, personal property like art, jewelry, or collectibles may require specialized appraisals, which can run into the thousands. Many heirs don’t realize that even selling a family car from the estate can trigger administrative costs — title transfers, DMV fees, and sometimes even emissions testing requirements, all of which must be paid before the asset can be liquidated.

Account closure penalties are another overlooked expense. Some brokerage accounts charge inactivity or closure fees if not managed promptly. Mutual funds or annuities may have surrender charges if withdrawn within a certain period. I discovered this when trying to consolidate my mother’s old retirement account — a 1% surrender fee applied because the contract was less than seven years old, costing over $1,200 on a $120,000 balance. That fee could have been avoided with a direct rollover, but I didn’t know the option existed at the time.

Transfer taxes vary by location but can be significant. While the federal government does not impose inheritance taxes, six states — Iowa, Kentucky, Maryland, Nebraska, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania — do. Rates range from 1% to 18%, depending on the relationship to the deceased and the size of the inheritance. Real estate transfers may also incur local recording fees or deed stamps, which are based on property value. These are not one-time surprises; they compound. A $500,000 home could face $5,000 to $10,000 in combined transfer and recording fees alone. The key is anticipation: knowing these costs exist allows you to plan for them, rather than react in the moment. Ignorance is not innocence — it’s financial risk.

Tax Traps Waiting in Plain Sight

Taxes are often the largest single cost in an inheritance, yet they are the most misunderstood. Unlike income, inherited assets are not subject to federal income tax upon receipt — but what happens next can trigger major tax events. The most critical concept is the **stepped-up basis**. When you inherit stocks, real estate, or other appreciated assets, the cost basis is reset to the market value at the date of death. This means that if your loved one bought a home for $100,000 and it’s worth $500,000 when they pass, your cost basis becomes $500,000. If you later sell it for $520,000, you only pay capital gains on $20,000 — not the full $420,000 appreciation.

This rule is a powerful benefit, but it only applies if you understand and preserve it. Many heirs unknowingly void this advantage by making mistakes in how they transfer or manage assets. For example, if you withdraw funds from an inherited IRA and deposit them into a personal account, the entire amount may be treated as taxable income in that year. One woman I know inherited a $180,000 traditional IRA and withdrew the full amount within three months, believing she had a one-time tax-free window. Instead, the withdrawal pushed her into the highest tax bracket, resulting in over $50,000 in federal and state taxes — a loss of nearly 30% of the inheritance.

Retirement accounts are especially tricky. Inherited IRAs must be handled under specific IRS rules. Spouses have more flexibility — they can roll the funds into their own IRA and defer withdrawals. Non-spouse beneficiaries, however, must follow required minimum distribution (RMD) rules based on their life expectancy or withdraw all funds within ten years, depending on when the original owner passed. Failing to take RMDs on time results in a 25% penalty on the missed amount. These rules are not optional; they are enforced strictly.

Then there’s the potential for estate taxes. While only estates above a high exemption threshold — currently over $12 million for individuals — owe federal estate tax, some states have lower thresholds. For example, Oregon and Massachusetts impose estate taxes on estates over $1 million. If an estate exceeds these limits, the tax is paid before assets are distributed, reducing what heirs ultimately receive. The takeaway is timing and method: when and how you access inherited assets can determine whether you keep the majority — or lose a significant portion to taxes.

Asset Allocation After Inheritance: Rebuilding the Portfolio

Inheriting a portfolio means inheriting someone else’s financial strategy — one that may no longer align with your goals, risk tolerance, or timeline. My mother’s investments were heavily weighted in dividend-paying utility stocks and CDs, a conservative mix suitable for her retirement income needs. But at 48, with two children in school, my financial picture was different. I needed growth, not just stability. Yet, I almost kept everything as-is, out of respect and fear of making a mistake. That would have been a disservice to both her legacy and my family’s future.

Rebalancing an inherited portfolio should not be a reaction — it should be a recalibration. The first step is evaluation: assess each holding’s purpose, performance, and cost. Are the assets diversified across sectors and asset classes? Are fees eating into returns? Is the risk level appropriate for your stage in life? For example, holding a concentrated position in a single stock — even if it was your father’s company — exposes you to unnecessary risk. Diversification is not just a principle; it’s a protection.

The next step is transition. This is where costs can creep in. Selling assets triggers capital gains taxes if the stepped-up basis is not properly applied. Frequent trading adds brokerage fees. The smart approach is to rebalance gradually and tax-efficiently. Consider in-kind transfers — moving assets between accounts without selling — to avoid triggering tax events. If selling is necessary, prioritize assets with the highest cost basis to minimize gains. Use tax-loss harvesting if you have losing positions elsewhere to offset gains.

I worked with a fee-only financial advisor to map out a five-year rebalancing plan. We shifted 15% of the portfolio annually into low-cost index funds and international equities, maintaining stability while increasing growth potential. We kept some of her dividend stocks for income but reduced exposure to single-name risks. The result? A portfolio that honored her conservative instincts while supporting my family’s long-term goals. The key was patience: rebalancing doesn’t have to happen in a month. It should happen thoughtfully, with cost and tax efficiency as guiding principles.

When to Hold, When to Sell: Making Cost-Aware Decisions

Not every inherited asset deserves a place in your financial life. Sentiment can cloud judgment, leading to costly attachments. That family cabin by the lake may hold memories, but if it requires $8,000 a year in maintenance, property taxes, and insurance, it’s not a legacy — it’s a liability. The decision to hold or sell should be based on three factors: utility, cost, and alignment with your goals.

Real estate often presents the hardest choices. If you don’t live near the inherited property, management becomes a burden. Rental income may not cover expenses, especially after accounting for repairs, vacancies, and property management fees. One study found that 60% of inherited homes are sold within three years, often because heirs realize the hidden costs outweigh the benefits. If you choose to rent, understand landlord responsibilities, local regulations, and tax implications — including depreciation recapture when you eventually sell.

For investment accounts, evaluate performance and fees. High-expense mutual funds or underperforming stocks should be scrutinized. If an asset isn’t contributing to growth or income, and it’s expensive to maintain, selling may be the wiser choice. But do so strategically. Avoid selling large positions in a single year to prevent jumping into a higher tax bracket. Spread sales over multiple years if possible.

Retirement accounts like IRAs and 401(k)s should generally not be liquidated unless absolutely necessary. The tax cost is too high. Instead, consider rolling them into an inherited IRA to maintain tax-deferred growth. Withdraw only what you need, when required, to minimize tax impact. The goal is not to eliminate assets — it’s to ensure each one earns its place in your financial plan.

Smart Moves That Cut Costs and Protect Value

Preserving inherited wealth isn’t about chasing high returns — it’s about avoiding preventable losses. The most effective strategies are often the simplest: consolidate accounts, reduce fees, and seek objective advice. Multiple accounts mean multiple fees — annual maintenance charges, trading costs, and advisory fees. Consolidating brokerage, bank, and retirement accounts into fewer institutions can reduce these expenses significantly. Many large financial firms offer fee waivers or reduced costs for higher balances, making consolidation both practical and profitable.

Adopt low-cost investment tools. Index funds and ETFs typically have expense ratios below 0.20%, compared to actively managed funds that can charge 1% or more. Over 20 years, that difference can cost tens of thousands in lost returns. Automated rebalancing services, offered by many robo-advisors, maintain your target allocation without emotional interference or excessive trading. These tools are not flashy, but they are effective.

Work with a fee-only financial advisor — one who charges a flat rate or percentage of assets, not commissions. Commission-based advisors may recommend products that benefit them, not you. A fiduciary advisor, legally bound to act in your best interest, provides objective guidance on tax planning, asset allocation, and estate strategy. The cost — typically 0.5% to 1% of assets annually — is often offset by the value of avoided mistakes.

Use custodial services for inherited accounts. Naming a custodian ensures proper management, especially if minors are involved or if you’re coordinating with siblings. It also maintains legal and tax compliance. These services, offered by banks and brokerage firms, charge modest fees but provide structure and peace of mind.

Building a Legacy That Lasts — Beyond the Initial Transfer

True financial stewardship extends beyond the first year of inheritance. Preserving wealth means creating systems for ongoing management, documentation, and succession planning. Start by organizing all records — account numbers, passwords, legal documents — in a secure but accessible place. Consider a digital vault or estate planning service that allows trusted family members to access information when needed.

Document your decisions. Why did you sell the house? Why did you keep certain stocks? Writing this down helps justify past choices and guides future ones. It also protects against family disputes, which can arise when intentions are unclear.

Prepare the next generation. Talk to your children about the inheritance, not just the amount, but the values behind it. Teach them about responsible management, the cost of poor decisions, and the importance of planning. Consider setting up trusts or educational accounts to extend the legacy in a structured way.

Inheriting assets is not the end of a financial journey — it’s a new beginning. The real victory isn’t in receiving wealth, but in preserving and growing it with wisdom. Every dollar saved from unnecessary fees, every tax-efficient move, every thoughtful decision — these are the quiet acts that honor a legacy. This is not about getting rich quickly. It’s about building something lasting, one careful choice at a time.